This Is What You Want... This Is What You Get

A few words about the sound of 'Marty Supreme'

Somewhere in the thrumming sound of ‘80s synths lies a heartbeat. It was, and still is, the sound of the future. Experiments in electronic music date back as early as the late 19th century, and like much that grew out of the peak of the industrial age, it represented what in many ways is still the bleeding edge. A plain expression of human mastery over nature, to harness and supersede the bounds of the physical world for artistic means. Cinema grew out of the same stew of Belle Époque invention, chemically capturing light on celluloid strips and birthing whole new realms of art.

I remember the first time I watched Forbidden Planet, alone in my room, the big old CRT across from my bed. The electronic score knocked me out. It had never occurred to me that such music was being produced in 1956, never mind used so boldly, as though part of the film’s tapestry of sci-fi sound effects rather than anything resembling a symphonic score.

Louis and Bebe Barron’s music for Forbidden Planet was a watershed in cinema and sound. It drew from their work in the avant-garde space earlier in the ‘50s, scoring short films like Ian Hugo’s “Bells of Atlantis,” in which the bleeping and blooping of their cybernetics circuits portended a new sound to accompany a new cinema.

A few years later, Dutch composers Tom Dissevelt and Kid Baltan were out there dropping beats, pushing electronic music closer and closer to the pop music space, anticipating the likes of Kraftwerk by more than a decade.

Coming out of the Second World War, the future was something more than a dream. As American culture began cloaking itself in the prudish image of suburban pleasantries, exporting “the good life” around the world, visions of technological salvation and a new way of being took hold of the public imagination. There’s a relatively straight line between Harry Revel’s theremin-infused experiments on 1947’s “Music Out of the Moon” album, and the audacious imagining of humanity’s next millennium in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

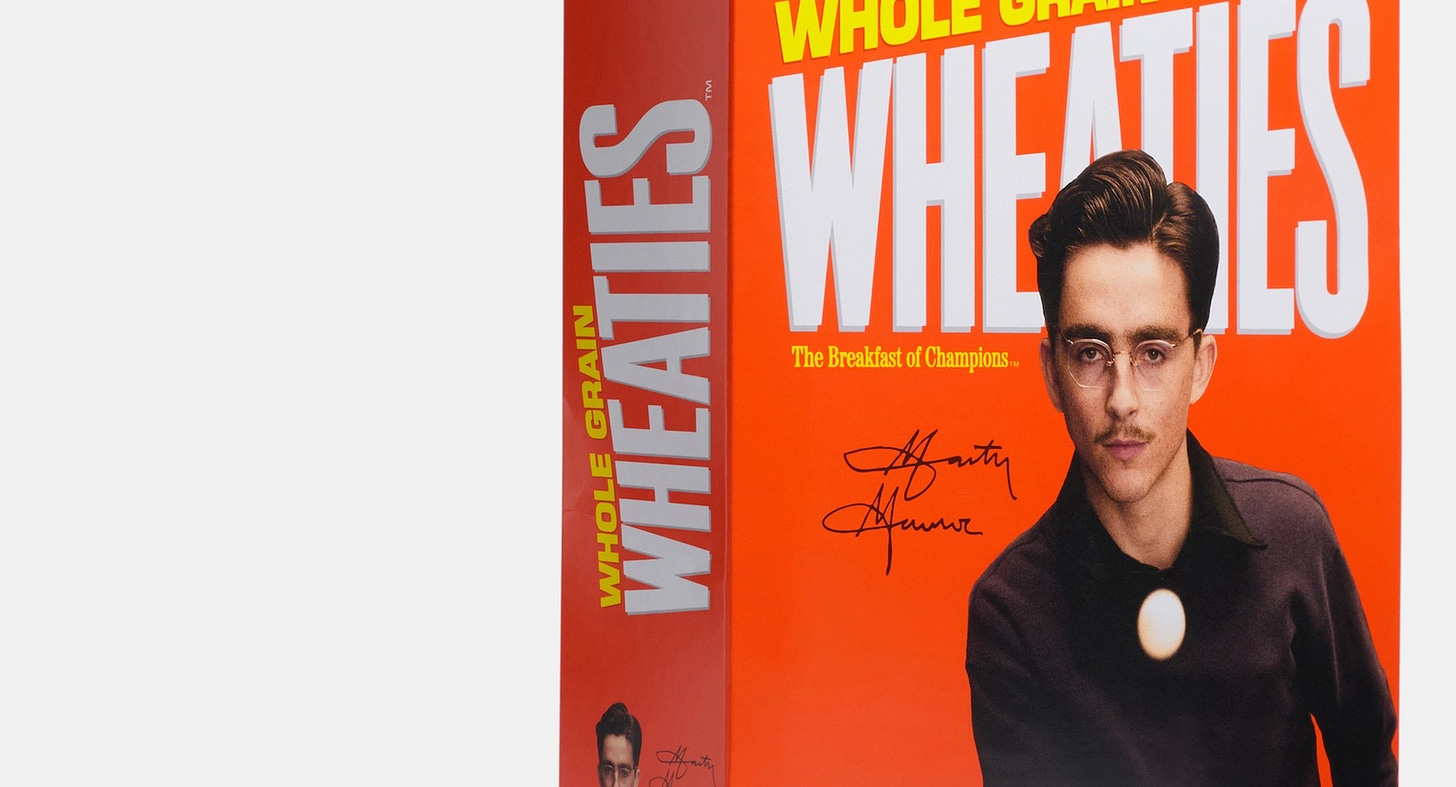

So much promise, and then the ‘80s, during which the culmination of capitalist theory begat a more base futurism embodied in consumption and personal branding. It’s the world we’re still living in, stuck as we are in perpetuations of pasts we long for, cycling through fashion to recapture whatever forward-looking spirit we feel lacking. If Fukuyama’s End of History failed to emerge from the revolutions that marked the transition out of the ‘80s, his analysis perhaps better captured the pervasive sense in the post-Cold War decades that some fundamental yearning has died out, subsumed into inhuman dynamics of buying and selling. To strive in this era is to demand, not the future, but purchasing power, or, better yet, brand power. The cover of a Wheaties box.

In Marty Supreme, Timothée Chalamet plays Marty Mauser as a young man out of time. His striving is instantly recognizable as modern, but he lives in the 1950s. Bridging the gap is a score by Daniel Lopatin that draws from the ‘80s synth sound, along with a suite of ‘80s needle drops whose anachronisms define the character and the film. Marty’s brash, assholish, narcissism might have been off-putting, but for the heartbeat mirrored in his musical accompaniment, which signals something eminently relatable. What he wants is a place in a future. He wants to be the future. Out of the shadow of the Holocaust, and in the depths of mid-century, urban American poverty, Marty is after something totally new, some undiscovered country where his freedom feels all his own, unaccountable to the forces keeping him grounded. When the lyrics of Public Image Ltd.’s “The Order of Death” blast through the soundtrack—“This is what you want/This is what you get”—it is as though the movie is speaking back to him: “The future is coming, but it doesn’t belong to you.”

“The Order of Death” was originally meant to soundtrack the 1983 Harvey Keitel film Copkiller, in which PiL lead singer John Lydon also stars. If The Sex Pistols helped take rock music down to gritty basics, Johnny Rotten formed PiL to inject more experimental flavour into his punk stylings. It was the New Wave, the evolution of punk’s simple cynicism into the embrace of further horizons. The song contains the tension of that evolution, equally foreboding and exciting. It still sounds fresh. It still sounds like the future.

Marty Supreme ends on a very different synth-laden ‘80s track, though. “Welcome to your life,” are the first lyrics of Tears for Fears’ “Everybody Wants To Rule The World,” one of the great singles of the era, and one whose themes are almost too perfectly in conversation with Josh Safdie’s film. Its sound, too, recapitulates Marty’s journey, in which experimentation coalesces into its opposite. The strange modulations of the Barrons’ work gives way to lush, easy listening. It’s expansive, and comforting, and sentimental, even as its lyrics lay bare the corrupt influence of power driving society. As those synths begin to play and Marty stares into the eyes of his newborn son, reality sets in. No more striving for the future; it’s already arrived.

Damn, this was brilliant, especially the insight about the '80s synths being both a heartbeat and a funeral march. I remember watching old films w synthesizer soundtracks and feeling like they were almost prophetic—how tech could amplify human expression but also flatten it into commoditization. The way thesoundtrack here tells Marty his future isnt really his own kinda nails the paradox of striving for individuality in a world built on mass consumption.

You should do more music writing, Corey, this was really wonderful. Your discussion of PiL reminded me of a formative music book: have you ever read Rip It Up and Start Again by Simon Reynolds? It charts the formation of post-punk into new wave, and the resulting cultural crash-out.