Certified Copy

A few words about 'Peter Hujar's Day'

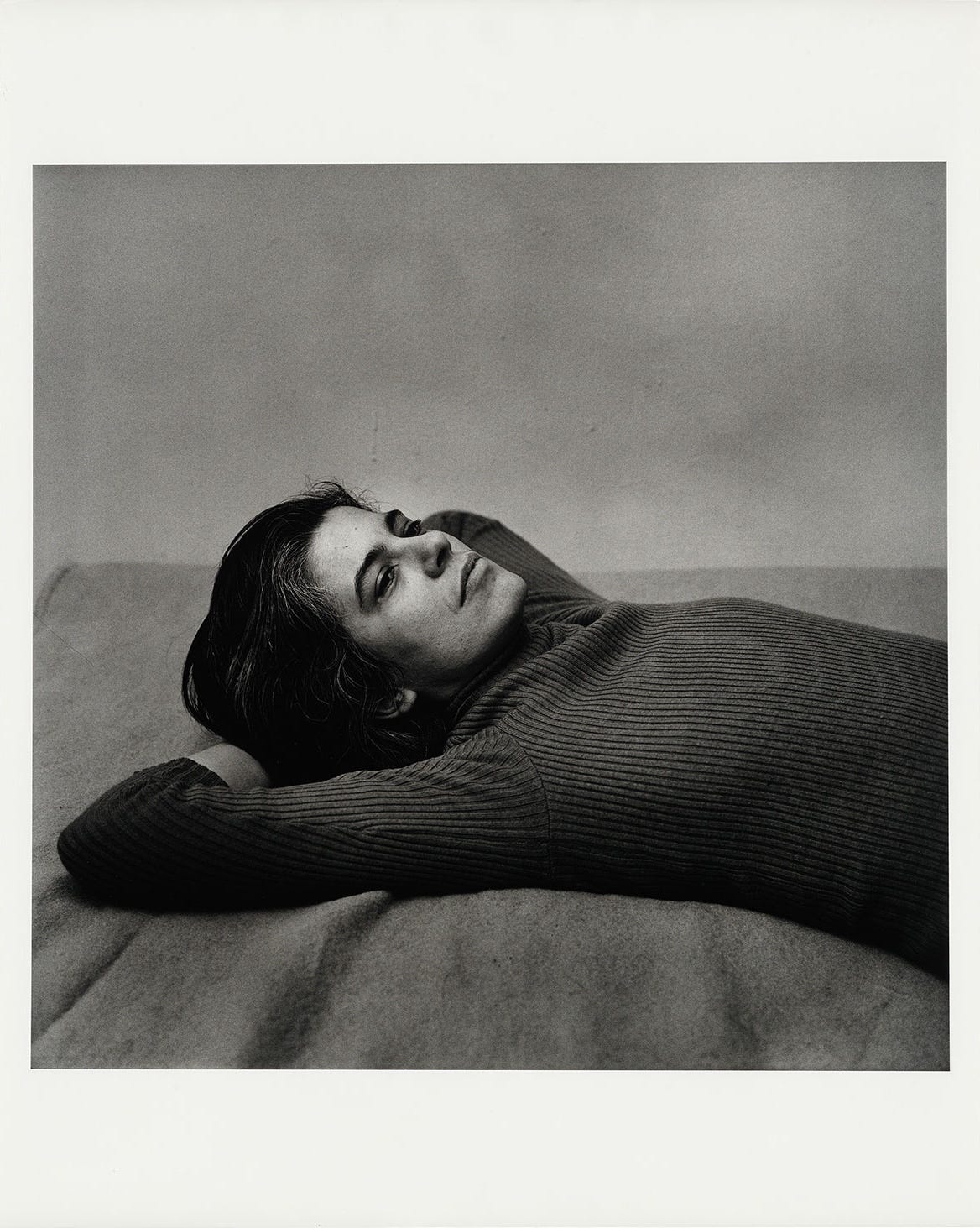

Peter Hujar took this extraordinary photo of Susan Sontag. In the frame is nothing. A wall, a bed draped over by a felted coverlet, and Sontag. She lies back, her corduroy turtleneck stretching its lines out over her body, her arms back, hands under her head. On her face is a blank sort of expression, but not really blank, and not really neutral. There is work behind her eyes—not unexpected for a great thinker—staring off to some middle distance. I’ve long loved that photo. It captures some ravishing essence in Sontag, a romantic ideal of beauty and intellectualism in the simplest of form. The emerging gray streaks in her hair add texture, accentuating the photograph’s spare but lived reality. Perfectly posed; pure nature.

In the spirit of Hujar’s work, director Ira Sachs has crafted a stunning new portrait of the photographer. Peter Hujar’s Day is based on the book by Linda Rosenkrantz, in which she publishes the transcript of an interview she conducted with her friend. It had originally been intended as a wider project. She would interview her artist friends, in detail, about everything they did the day prior. Hujar was the first of these interviews, which would have been collected in a book. The interviews mostly never happened, the book came to nothing, and the tape was lost. But a transcript was found, the opening titles of the film inform us.

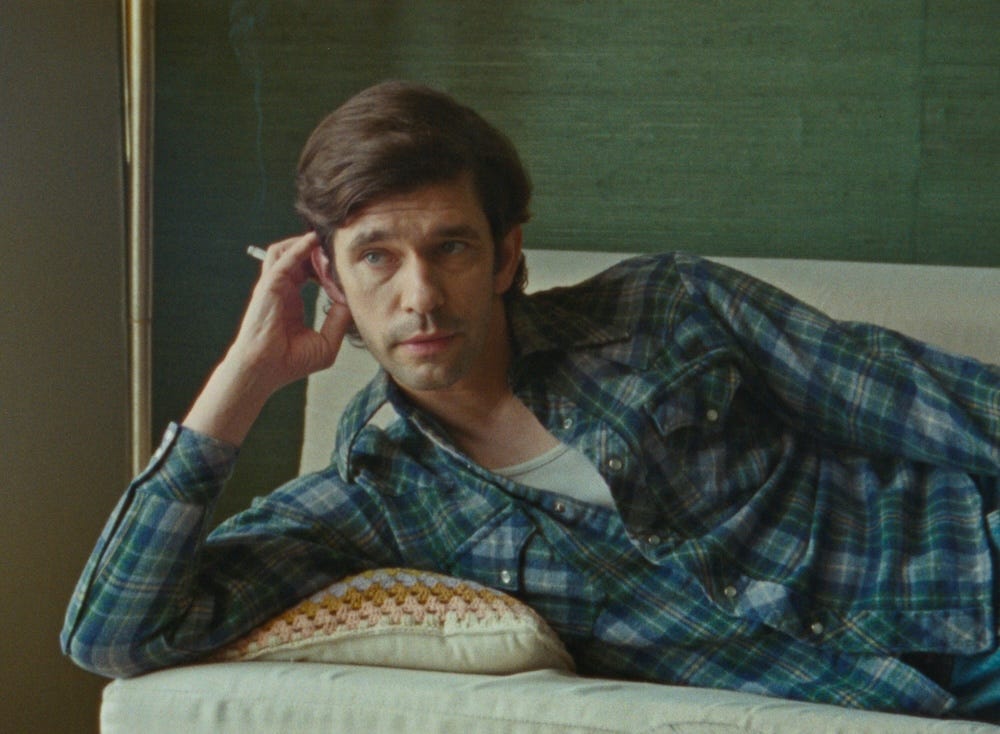

From that transcript, Sachs reconstructs the interview for the screen, with Ben Whishaw playing Hujar, and Rebecca Hall as Rosenkrantz. Along with the title cards providing key context, the film opens with a nod to its own artifice. Reconstruction is, in fact, a form of construction, and Peter Hujar’s Day exists in the tension. A man recounting the day before; recorded onto tape; translated into transcription; written out as dialogue in a script, interpreted and performed by actors; staged, filmed, and assembled. A copy of a copy of a copy, and a game of artistic broken telephone, where the interpretation becomes additive.

Hujar’s ghost haunts Peter Hujar’s Day. He died in from AIDS in 1987, age 53. He left behind his photos and his friendships, the entry point for an attempt at understanding. Rosenkrantz’s idea, to capture in text the daily doings of her cohort, was premised on the notion that some truth might resolve itself in the process. That more, perhaps, might be gleaned from a person considering the mundanity of their daily actions. On the day in question, in a New York City apartment in 1974, Hujar reflects on his adventure heading out to photograph Allen Ginsberg. If the day was special, it was only defined by that. But he digs further, recalling his entire day, morning to night, including his call with Sontag, his hours in the darkroom, his odd lack of appetite throughout, all of it. Slowly, slowly, a picture emerges of a man naturally concerned with the finer details of things, often living in his own head, offering whole narratives of thought about the situations he encounters. He’s a man of incredible observation and articulation, no doubt the source of his photography’s depth.

The real interview was done in a little over an hour, with Hujar and Rosenkrantz just sitting at a table. Sachs does not adhere to fact, only the words in the transcript. In a series of scenes and tableaus, he has the pair traverse every corner of the apartment they shot in, done up in great ‘70s style. As they shift locations, the day shifts, too. An hourlong interview stretches across a whole day, as the light in the apartment changes, and the characters grow more tired and more open. As it goes, the film becomes more mannered, more open to its own artifice. The performances, at first attempting something like facsimile, morph into more expressive interpretations of character. Late in the film, Hujar describes getting up in the middle of the night, awoken by two prostitutes talking loudly outside his window. He describes looking out to the street below to watch them. A tossed off sort of aside in the transcript, but here it is the heart of the film. Something Hujar connected with, and in that connection preserved a moment and the anonymous people in it, transported through time to a cinema screen fifty years on.

It’s cinema and art as dialogue with the past, and with the people who occupied it. When tears stream down Rebecca Hall’s face at the end of the film, nothing in the transcript would suggest such emotion, yet these emotions are true nonetheless. Reflecting the relationship between Rosenkrantz and Hujar, and between Sachs and his subjects, and Hall and hers. It’s elegiac, and expansive. The form of the film, with its carefully orchestrated scenes, resemble aspects of Hujar’s work, adding colour and new texture, all of it invented. Even the accents are invented, Sachs having cast two Brits to barely impersonate two Americans. The historical record of a moment in time and place becomes an imaginative space for empathy and human feeling. An astonishing culmination of Rosenkrantz’s initial concept.